RE Course - 7.01 - Virtual Memory

7.1 Virtual Memory

You’re probably aware that a computer has physical memory, also known as RAM. But how is this memory accessed? Well, with addresses of course! Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

- If multiple processes are running on the system, you need some way to specify the memory regions for each process.

- You also start to run into issues with space. What do you do if you only have 4GB of physical memory but the processes running need 6GB?

- If programs aren’t loaded into the same address space every time they run, then hard-coded addresses won’t work.

- What about fragmentation? If a small program exits and there isn’t enough room for a new process in that now free memory region, that’s just wasted space. Even if a process is small enough to fit in that space, unless it’s the same size, there will still be unused memory.

To solve these issues, and many others, what if every process could run as if it was the only process on the system? This is where virtual memory comes in.

What Is Virtual Memory

Virtual memory allows every process to run under the illusion that it’s the only process running and has access to all of the system’s memory.

To make this illusion happen, processes run as if they’re loaded at a specific address, such as 0x40000000, no matter where they are actually loaded in physical memory. The memory where processes think they’re located in is called virtual memory. When a process tries to access memory, it’s accessing virtual memory. The address a process is trying to access is converted from a virtual address to a physical address by the Memory Management Unit (MMU).

Example:

A process thinks it’s running at 0x40000000 (virtual memory) when it’s really at 0x20005000 (physical memory). When the program tries to access the virtual address 0x40000124 the MMU translates that to the physical address 0x20005124. This is done because the system recognizes that the process is trying to access an address that is located at the offset 0x124.

This allows a program to be loaded anywhere into memory (as long another process isn’t loaded there) and it can use memory as if it was the only process.

Another fancy thing about virtual memory is that it can map processes in chunks. For example, part of the process could be at 0xB0004500 to 0xB000F000 and another part could be at 0xD0100000 to 0xD010C000. Another process could be located in between those two chunks, such as from 0xC0000000 to 0xD0000000.

With that vague understanding of virtual memory, let’s get into some more detail.

Pages

Mapping every physical memory address to a virtual memory address individually would, ironically, take up too much memory. Instead, physical memory is usually divided into 4KB chunks called pages which are mapped to virtual addresses. These pages and their information are stored in page tables. Pages are quite complex, but for our purposes, we only need a simple understanding of them. Also, there are small and large pages that are 4KB and 2MB respectively. Large pages are typically used for core Windows components and I/O.

The mapping of these pages from physical addresses to virtual addresses is done by the Memory Management Unit (MMU). The MMU is a physical piece of hardware that, on conventional desktop computers, resides in the processor.

Protections

Each page has set privileges including read, write, execute, or a combination of those. For example, a page that contains data might be marked as read/write. This can be an issue when one page contains both data and executable code. In that case, the entire page would have to be marked as read/write/execute.

Page States

Pages in virtual address space can be free, reserved, committed, or shared. Committed and shareable are the “normal” pages and both map to valid pages in physical memory. Committed pages are slightly different because they cannot be shared by processes. Instead, they are private, or committed, to only one process. Committed pages are also known as private pages for that reason.

Address Translation

Now for the fun part, how virtual addresses are mapped to physical addresses.

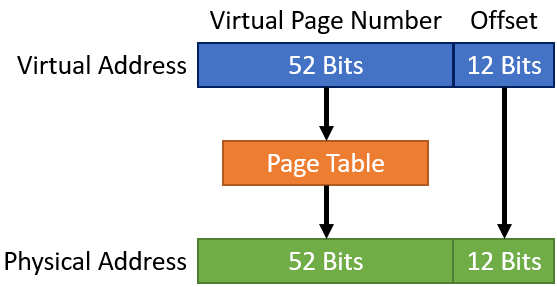

Each table entry is broken into 2 parts. The bottom twelve bits are the page offset. The rest is the virtual page number. The remaining 12 bits are not translated and instead are treated as an offset.

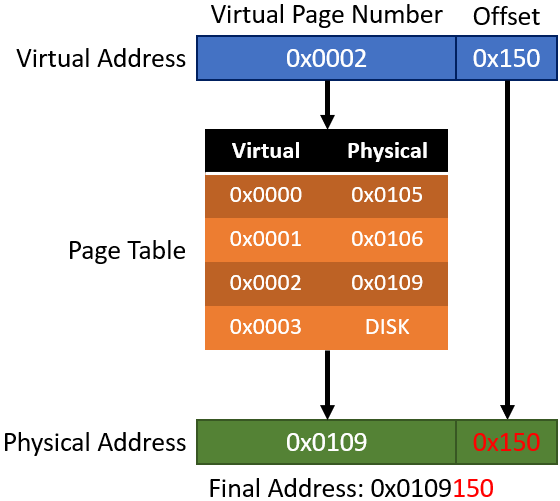

Here’s an example (simplified and not completely accurate so it’s easier to understand):

Here’s what’s going on step-by-step:

- The process is trying to access 0x0002150.

- The address that will be looked up in the page table (virtual page number) is 0x0002.

- The offset is 0x150.

- 0x0002 will be looked up in the page table and it will be translated into 0x0109.

- From 0x0109 the offset 0x150 will be added.

- The result is 0x0109150.

You may also notice that under the physical address list there is “DISK”. This is because pages can be put onto disk if there isn’t enough physical memory.

There it is, the basics of virtual memory. Hopefully, it wasn’t too painful.

You Don’t Have Enough RAM

On x86 each process is told it has 4GB of memory, half for kernel-mode the other half for user-mode. This already presents a pretty obvious issue. With a mere 20 processes running, you would need 100GB of RAM. Well, it gets worse. With modern x64 Windows, each process is allowed to have 128TB of memory. Ironically the Windows Server 2016/2018 Datacenter only supports 24TB. Now, of course, a process will probably never use that space but it’s still quite interesting. Thank you virtual memory!

Other Explanations

Here are some other resources that deal with virtual memory:

- https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/cse378/09au/lectures/cse378au09-23.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLiwt1iVUib9s2Uo5BeYmwkDFUh70fJPxX

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2quKyPnUShQ

- https://www.bottomupcs.com/virtual_addresses.xhtml